Let’s be neighbours: What Sebastián Auyanet is learning about building for neighbourhoods in Montevideo

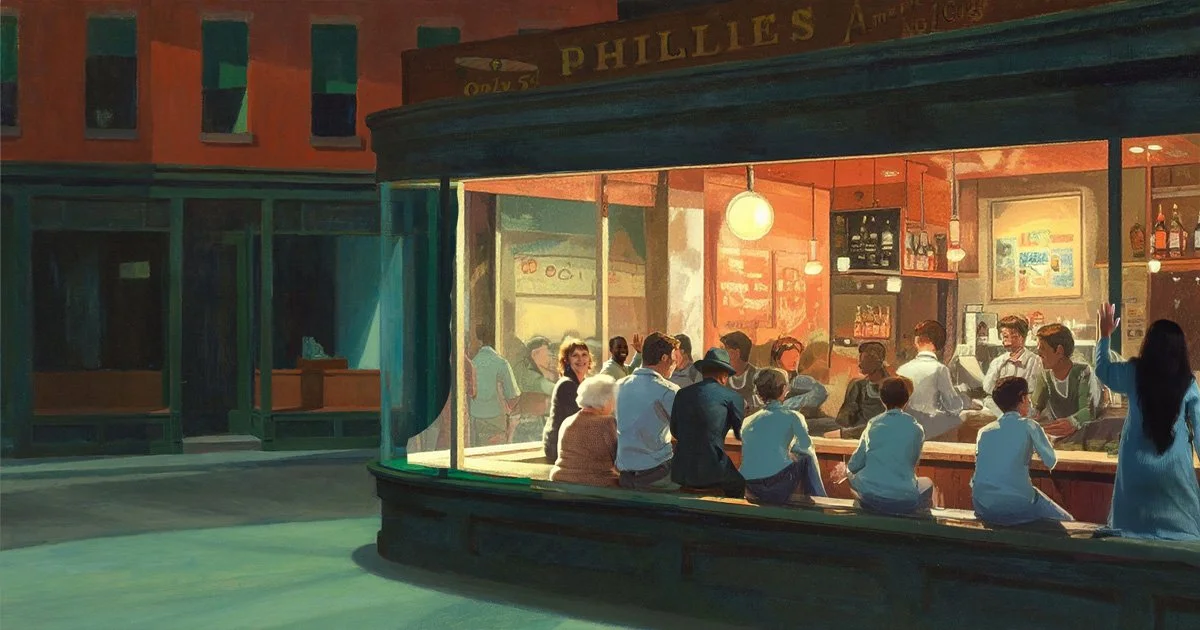

A short walk away from you is a place that was built for community. It might look like a pub or a café. Or a bench. Or a diner. What it really is is an opportunity to have somewhere to sit, look someone in the eye, and ask, “How are you? Are you okay?” Image (with apologies to Edward Hopper) by Rishad Patel using generative AI.

“Wait, wait, wait!”, I say to Sebastián. “You saw this in a Ken Loach film. You felt it in Bristol pubs, and in a small football stadium. You wanted it in Perugia. And now you’re going to build it?”

I am talking to my friend Sebastián Auyanet about a thing he is building. Sebastián lives in Montevideo in Uruguay, he has an insanely cool son, and an acute accent in his name. We've met IRL barely a couple of times, but we are quite devout about making time to talk to each other online because we’re really very good friends. We have wonderful rambling conversations, we find a lot of things quite funny (especially ourselves), we are deeply curious about each other — and about the world.

Sebastián is not building a startup. He’s building a small, slow thing: a community, maybe. He’s doing it with no money, no roadmap, and no grand pitch deck — yet. Currently it’s looking like a WhatsApp bot, a café, and a problem to solve: that we’ve forgotten how to be neighbours.

Chicharrones

When Sebastián and I have our chat about community, we aren’t talking about engagement funnels or growth metrics. (He’s also good with those.)

We’re talking about belonging. In fact, I think what he and I are really talking about is that we both have this intense need to belong to something much larger than us. I think it’s probably because we have complicated families; because we both identify as outsiders pretty much everywhere; and because we spend a great deal of time alone.

It’s possible that we like to belong.

Sebastián is telling me about The Old Oak, a Ken Loach film set in a former mining town in northeast England, where the rapidly shrinking working-class population struggles to welcome new Syrian refugees. In the film, the pub becomes the last stand for local identity — and a possible bridge between two fractured communities.

It resonates with him, he says, because he’s just been to England to visit his partner. In the pubs of London and Bristol, he rediscovers what a functioning community space looks like.

Sebastián Auyanet is an audience development, product, and impact consultant. Photo supplied

He’s telling me: “The whole experience threw me back again to how we talk about physical space and community. Like, how do we get physical about that?”

“I think that that to me pubs are the the real thing. So when you see working pubs in cities like London, Bristol, Oxford — to me, this is a beautiful thing. The very fact that you can go to this lovely place that looks like a church but they give you beer. And you can go at 7 am for breakfast. And you can read a book or you can have your tea. It doesn't even have to be about alcohol.”

“Pork scratchings”, I say, adding nothing to the conversation. “Chicharrones”, we both say together.

I like pubs. You can take your auntie there for her birthday. You can watch the game and yell at the tv with your friends. The woman behind the bar calls you “luv” — and yells at the tv with you.

Sebastián sees it at a small football match in the outskirts of London too—“local and opposition supporters are all blended together. There's a ton of great food stands around the stadium, a tiny stadium, and no one cares too much about the result.”

Shortly afterwards, at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, he realises he was trying to chase that same feeling again.

Bristol, but in Montevideo

So how do you bring that feeling — that pub — to Uruguay, a country without pubs? You don’t. You start with what you have.

Like so many of us, Sebastián has a favourite café. It’s near the school where his son goes. He knows the owner, he knows the regulars. So now, he’s building something that replicates that by convening people who want that back in their lives.

This isn’t a conversation about the Third Space, that space we tend to seek out that isn’t work or home. It’s more about collective ritual, the shared vocabulary, the inside joke, the artefacts of a civilisation that we build together without even knowing that that’s what we’re doing.

But how do you recreate two hundred years of community and ritual and cultural identity in these fractured world we live in? And how do you bring people together around it? Sebastián says, “Light needs to enter in this particular kind of way. The furniture needs to be just perfect and beautiful. You can’t install, like, a ritual.”

Exactly. My guess is you focus on the need for belonging, and the different ways in which we all need it.

He might add a hyperlocal information element to the mix, possibly a daily WhatsApp broadcast powered by a bot that scrapes information about the area, adds context, and sends it out at 8 am. A human in the loop — Sebastián (“because I have nobody to help me do this currently”) — reviews each post. He’ll add extra context too: “this shop’s closing,” “that road’s under repair,” “there’s a new playground.”

The feed is just an extra, a feature to be tested. What’s more important is how people convene around these conversations — and what happens afterwards in the form of decisions, action, collaboration.

So once a week, Sebastián plans to work out of that café — two hours, always the same two hours. If someone from the neighbourhood wants to drop by and talk, they can. “Office hours,” he says. “The chatbot does all the heavy lifting and I do the more interpersonal thing. We might even do an event once a month. Which really means: bring 10 people and let’s talk about the neighbourhood. And maybe if this gets traction, then maybe every six months, we would tackle more ambitious things. And if no one shows up, that’s fine. I’m there anyway.”

It sounds to me that the thing that he is building is testing people’s need to be better neighbours — or to find better neighbours. And maybe this is what builds better neighbourhoods.

Once a month, he might host a gathering. If people are showing up and finding it useful, they’ll talk. Maybe they’ll organise to fix the pothole, build the new playground, zone the parking spaces. Maybe someone will print a little flyer to put all of this information in it — or ways to replicate the same systems in your own neighbourhoods around the world.

I can’t think of a better way to bring people together.

There’s no pitch deck — yet

There’s a real business model here somewhere. That will come from Sebastián’s ability and intention to start super small, one neighbour at a time, one cafe and neighbourhood at a time. The point is to build from need and care.

“This isn’t about content,” we both said, semi-simultaneously. “People don’t care about content. They care about water pressure, and broken footpaths, and whether someone can fix the electrical box.”

My product-design obsessed brain is wondering if this could be a template. You could make a DIY kit for neighbourhood info, collaboration, and conversation. All you need is an AI scraper bot to find new neighbourhoods to test appetites, frustrations, and needs, a chat group, and a bit of consistency. And Sebastián.

Let’s be neighbours

Sebastián isn’t calling this anything yet. But it’s clear to me that he’s building the thing he wants in his own life — something rooted in place, around ritual, and interdependence. A space to look up from your phone and notice each other again.

So here’s the invitation:

A short walk away from you is a place that was built for community. It might look like a pub or a café. Or a bench. Or a football club. What it really is is an opportunity to have somewhere to sit, look someone in the eye, and ask, “How are you? Are you okay?”

Let’s be neighbours.

If you want to help build this thing with Sebastián, email him here.