Reporting on the Rohingya crisis? Here’s what you need to know.

What stays with me most are the masses of people, surreal in their scale. For the first two weeks of September, I covered the aftermath of a Burmese military security operation that drove half a million Muslim Rohingya across the border into Bangladesh.

On August 25, a militant group who call themselves the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked security posts in western Myanmar. Myanmar’s military retaliated against what they labeled “terrorism”. The United Nations has called the onslaught “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

Images of the exodus of exhausted Rohingya, with their elders and babies tied to their backs, are branded “fake news” and “performance art by drama queens” on Myanmar’s social media. While Burma’s citizens turn a blind eye to what is happening in Bangladesh, they accuse international media of pro-Rohingya bias and failing to strongly condemn ARSA’s violence.

Other journalists have been asking for tips on logistics and what they need to know when reporting on the Rohingya crisis. For those considering considering covering it from either side of the border, I’ve put together this guide based on the most common questions I’ve fielded. Due to the evolving nature of the crisis, things may have changed by the time you read this.

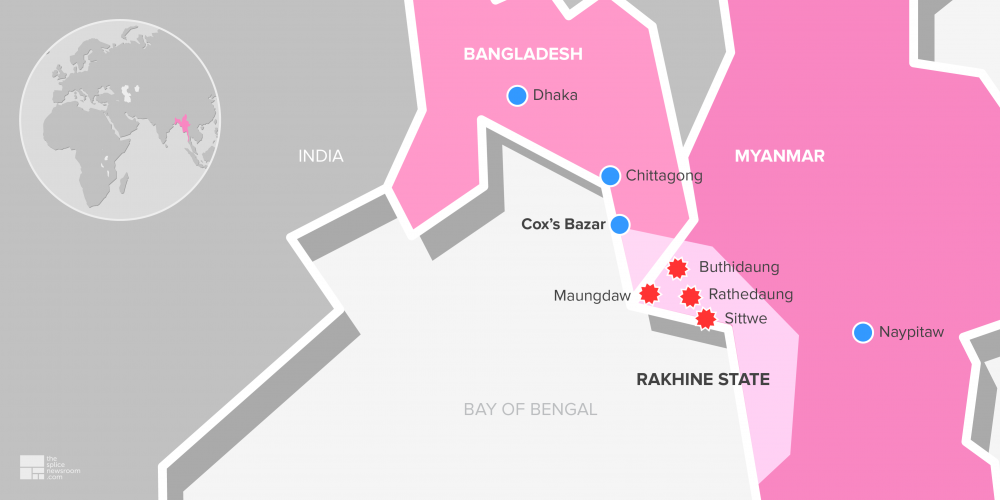

This map is a rough approximation of the regions depicted, is not to scale, and is for illustrative purposes only. Splice graphic: Rishad Patel

How accessible are the refugee camps in Bangladesh?

With a population of 163 million, Bangladesh is one of the world’s most densely populated countries and the influx of refugees is a huge burden. As a result, the government has—so far, at least—seemed keen to attract international coverage of the Rohingya crisis.

The standard route is to fly to Dhaka then take a domestic flight (about $50) to Cox’s Bazar the following morning. There are also direct flights from Bangkok to Chittagong, but the five-hour roadtrip from Chittagong to Cox’s Bazar is reportedly quite an adventure.

Cox’s Bazar is a popular beach destination for Bangladeshis, making it easy to find accommodation ranging from budget to high-end.

It takes at least one hour from Cox’s Bazar to the border region, depending on where you are planning to go. Travelling from one side of the affected border area to the other can easily take an additional 1.5 hours by car.

What about visa, fixers and cars?

While it was almost impossible to get a journalist visa for Bangladesh earlier this year, forcing reporters to travel on tourist visas, the process appears to have become easier. The army is restricting access for people without proper visa status. There have been recent reports that it is possible to obtain a journalist visa within two days at the embassy in Bangkok, but this can change.

Locals in Cox’s Bazar have developed an infrastructure for fixers and cars. The average day rate is about $150 for a fixer, and $60 for a car, depending on travel distances. You can also hire a tuk tuk (called CNGs in Bangladesh), which can be useful in some offroad areas where cars tend to get stuck. Both men and women fixers are available, and can be most easily found on Facebook.

The Rohingya refugees speak a language that is very close to Chittagonian, the dialect spoken in Bangladesh’s border region with Myanmar.

It seems like a tough subject to report on. What issues should I be aware of?

Monsoon rains, the distance between places and the sheer masses of people make it a physically exhausting reporting endeavour.

And of course there is an emotional toll. Colleagues who have covered crisis for more than 20 years say this is among the worst they’ve seen.

Journalists have penned a number of personal written accounts about the depth of feeling they’ve experienced covering the Rohingya crisis. What most describe is what psychologists call moral injury: feeling culpable for being present at an emergency situation without directly helping victims.

Try to keep the context of the crisis in mind—and, if possible, broaden your focus.

A flooded makeshift refugee camp in Bangladesh. Photos: Verena Hölzl

How can I report in a responsible manner?

Most importantly, never forget the emotional toll that our reporting places on the victims. Before asking children who lost their parents or women who were raped to recount horrific experiences, check the following guidelines from UNFPA, Columbia’s Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma and the Global Protection Cluster.

Also bear in mind that you are operating in a crisis zone with no space for privacy. Amid the crowded camps, I found it hard to provide interviewees with the safe and comforting environment that I would usually.

Is the conflict zone in Myanmar’s Rakhine State accessible?

No, at least not for foreigners. Even a local reporter who tried to gain access ran into serious trouble. Permission for journalists to go to Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung townships has not been granted in some time. While the government has organized press trips for some local and international media outlets, the UN’s human rights envoy has said that retaliation against Rohingya who speak out was a problem, meaning that journalists should weigh the risk to their sources before accepting such an invitation.

What should I know about going to Rakhine State?

There is a lot of hostility toward the international community in Rakhine State. When Kofi Annan, chair of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, arrived in September last year to investigate the situation in the region, protesters lined the road holding up banners condemning foreign interference. Things have worsened since the escalation of violence in August, when the government announced they were looking into allegations that foreign aid workers have been involved in terrorist activities.

The media has also been a target: a German TV crew that tried to do a live shoot from the state capital, Sittwe, in September was chased by a Buddhist Rakhine mob.

Be mindful of the risks. Sneaking into the cordoned-off Muslim quarters of Sittwe at night is not a good idea (yes, some journalists have tried it).

Irresponsible behaviour almost inevitably leads to access restrictions that impact your colleagues, and puts sources at risk.

Many in Myanmar have accused international media of pro-Rohingya bias, a claim that has a kernel of truth to it. How many stories about displaced Buddhist Rakhine have you seen? Pointing out that the media tends to focus its attention on those who are most victimized has not won over many critics of the coverage. Try to keep the context of the crisis in mind—and, if possible, broaden your focus.

TWEET